Image Credit: Iván Greco, Future of Fish Chile

Blue economy is a phrase used to describe the many ways that ocean and coastal resources provide economic benefits to humanity. The natural capital of these resources provides benefits that can manifest directly through livelihood activities like fishing and tourism or indirectly through natural ecosystem services, such as coastal protection, carbon storage, and biodiversity preservation, or practicing one’s cultural heritage. A sustainable blue economy is an economic model which emphasizes that ocean resources are managed and harvested in a way that safeguards their abundance for future generations. Taking it one step further, a just blue economy recognizes and ensures that coastal communities have equity, access, participation, and rights to the use and management of ocean resources that they rely on and that affect their well-being.

Small-scale fisheries (SSFs) are responsible for over half the world’s fish catch and account for 90% of individuals employed within the seafood sector, directly supporting the livelihoods of over 200 million people. Additionally, the importance of small-scale fisheries to food, nutrition, and income security in many low and middle-income countries (LMICs) makes it urgent that marine resources are managed sustainably. This is especially true in the face of major socio-ecological crises, such as climate change. However, the current health of many SSFs is in decline due to unsustainable fishing practices, much of which is driven by the ever-increasing global demand for seafood, putting SSFs communities and their people at risk.

To counter the effects of unsustainable fishing, fishery improvement projects have been launched and are active in many fisheries across the globe. Despite success in industrial fisheries (and some targeted high-value species like tuna), fishery improvement efforts are underachieving and often fail in SSFs. This lack of progress has multiple factors, as can be found in a recent assessment of fishery improvement projects from the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. Among the findings, the lack of fisher involvement, participation, and incentivization stand out as key barriers. We believe this is THE primary limiting factor in the success of fishery improvement projects in SSFs. After all, sustainability can’t be achieved without change on the water and at the source of where seafood is caught.

As a firm supporter of fishery improvement projects, we focus on understanding the limitations, concerns, and lack of capacity that fishers face in order to design solutions that can deliver tangible livelihood benefits. These solutions are being designed to complement fishery improvement projects by ensuring that fishers and seafood businesses adopt specific business practices for transparency including formalizing their businesses, adopting traceability technologies, and reporting their catch within regulations. In order to meet these dual needs, careful consideration is being given to ensure business solutions that derive benefits for fishers and seafood businesses do not lead to unintended consequences that further deteriorate sustainability. If designed appropriately and in collaboration with fishery improvement initiatives, this approach supports just Blue Economy principles by providing agency to fishers to both sustain and improve their livelihoods individually and collectively as a coastal economy as well as provide agency to manage their coastal resources in a more sustainable manner.

A powerful tool that we believe can provide agency to small-scale fishers to improve their livelihoods and business performance is the introduction of digital services. We define digital services as: services delivered via the internet or electronic network that are automated (and/or require minimal human intervention to use) and create benefits for users by simplifying common data collection, analysis, and application processes. Digital services can provide fishers with access to a range of knowledge and resources. All through their cell phone, fishers can receive guidance on industry best practices, seek out local resources, combine forces with fellow fishers to increase their associative strength, access new, more profitable markets for selling their products, and build their credit histories and apply for credit to scale their business over time. For fishers in remote and rural areas in LMICs, these resources provide fishers with greater market power, leading to more efficient, resilient, and autonomous livelihoods.

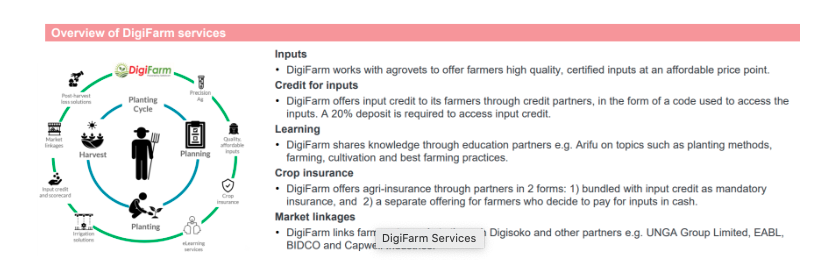

Though digital services have had little application in the fishing sector to date, one only has to look to the analogous industry of small-scale agriculture to find significant evidence indicating that increased access to digital services has been a game changer in the lives of smallholder farmers. One such compelling example is the success of DigiFarm, an integrated mobile platform for digital services, targeting Kenyan smallholder farmers.

Image source: The Impact of DigiFarm on Smallholder Farmers, MercyCorps | AgriFin

Over the last five years, DigiFarm has supported 1.3 million registered users to expand their businesses, save more, gain knowledge, and build capacity for external shocks. According to DigiFarm’s 2021 Impact Study, approximately 90% of users agreed or strongly agreed that DigiFarm had strengthened their capacity by equipping them with better farming knowledge and information, while approximately 75% of users acknowledged an improvement in their resilience because of using DigiFarm. In one instance improved resilience was demonstrated when DigiFarm helped users cope with a locust invasion, thereby illustrating that early and more comprehensive information can be an inexpensive solution to building resilience against shocks. Overall, in follow-up sessions, most farmers reported experiencing an improved standard of living as a result of their participation in the DigiFarm suite of digital services.

With digital services capable of providing significant benefits to fishers’ livelihoods, an incentive mechanism can be created for fishers to adopt new business practices. Using this as a leverage point for broader change, these digital service offerings would include compliance requirements for their access and use that support broader sustainability and equity initiatives such as fishery improvement projects. Most importantly, access can be contingent upon fishers having a legally registered business. This is essential as a majority of small-scale fishers operate in shadow markets. As more fishers formalize their businesses, their compliance requirements, whether to tax authorities, fisheries regulators, or downstream buyers, increase transparency across a range of stakeholders. Part of this transparency lies in the generation and sharing of data which can benefit governments in the monitoring and enforcement as well as fish stock assessment; by supply chains to meet traceability requirements and de-risk their trade; by investors to design innovative finance products built on the back of digital service platforms; and fishery improvement projects to monitor and assess the progress of equity and sustainability across the fishery.

This generation and sharing of data is essential to achieve these broader benefits of equity and sustainability in coastal fishing communities. It requires that digital systems are open and that data can be shared and interoperable to be beneficial to individual stakeholders as well as to initiatives to support the equity and sustainability of the fishery. This brings us back to the need for agency for fishers. Ensuring agency for fishers as leaders in these broad equity and sustainability efforts is essential. We believe strongly that when coastal communities have the agency to engage and lead in driving forward a just blue economy, their practices produce effects that positively emanate outward. For these communities, utilizing and honoring ocean resources is the heart of their community, the center of culture and traditions, and is woven into the fabric of everyday life.

References:

Arthur, Robert I, Daniel J Skerritt, Anna Schuhbauer, Naazia Ebrahim, Richard M Friend, and U Rashid Sumaila. “Small-Scale Fisheries and Local Food Systems: Transformations, Threats and Opportunities.” Fish and Fisheries 23, no. 1 (2022): 109–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12602.

Mercy Corps & AgriFin. “The Impact of DigiFarm on Smallholder Farmers,” May 26, 2021. https://www.mercycorpsagrifin.org/2021/05/26/the-impact-of-digifarm-on-smallholder-farmers/.

Pietruszka, D.K. “Blue Justice Infographic.” Too Big To Ignore:Global Partnership for Small-Scale Fisheries Research, 2020. http://toobigtoignore.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Blue-Justice_Infographic_2020_2.pdf.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. “Fishery Improvement Projects Workshop: Strategies, Successes, and the Future of FIPs – Global Economic Dynamics and the Biosphere (GEDB),” March 21, 2022. https://www.gedb.se/news/research-publications/other/fishery-improvement-projects-workshop-strategies-successes-and-the-future-of-fips.

Published Jun 30, 2022